Robin Vanbesien about the relation between art and politics in works by artists such as Rirkrit Tiravanija, Marcel Broodthaers, Peter Friedl, Sven Augustijnen, Willem de Rooij and Jonas Staal. Originally published in Dutch in the Belgian literary journal nY, #11 (Autumn 2011). Translated by Gregory Ball.

« Prisonnier de ses fantasmes et de son usage magique, l’Art orne nos murs bourgeois comme signe de puissance – il accompagne les péripéties de notre histoire comme un jeu d’ombres artistique, l’on s’en doute. »

Marcel Broodthaers, Être bien pensant ou ne pas être. Être aveugle, 1975

From the patio I can see a car with a Dutch number plate entering the Le Cézanne campsite. It is a Citroën Picasso, an MPV which came on the market in 2001 and stayed in production until 2011. It has no nose or tail; it is one complete smooth line. The model is also recognisable by the Spanish painter’s signature which adorns both sides of the prow and the rear door. It is a copy of one of more than one thousand Picasso signatures in existence.

The Dutch couple have to wait half an hour before they can check in. They take a seat at the large table on the patio where I too am sitting. These days, whenever I come across a Dutchman, I am sorely tempted to ask if he voted for Wilders. The same sort of curiosity also overwhelms me when I meet Flemish people. Did they vote for De Wever? It is a fairly innocent fascination. I always manage to stop myself just in time. It’s not normal to ask about people’s political persuasion. There’s something a little obscene about it.

In his role as head curator of the upcoming edition of the Berlin Biennale, the Polish artist Artur Żmijewski launched an open call to artists asking them to provide information about their political persuasion in addition to their portfolio. According to Żmijewski every artist has a specific political view, whether or not he or she can or wants to divulge it. This time things are different, he warns. Reality is shaped by politics, and so is art. Time to expose this so-called obscene background to art. Politics is the language for the collective needs that people share, writes Żmijewski. [1]

In every artistic practice the relationship with politics is defined in a personal or singular way. This coincides with the way in which the artist works and the imagined space that he or she creates. In the following pages and taking various works by artists as a starting point, I will describe the role and place of politics in their respective artistic practices. I see the imagined spaces that are generated by the artist’s practices as heterotopias. Michel Foucault introduced the term heterotopia, using the experience of the mirror. When we look in the mirror, we see ourselves in a virtual space behind the mirror’s surface. This inaccessible place is what Foucault calls utopia. At the same time, the mirror shows a real counter-movement in relation to the position that we occupy in front of the mirror. Foucault uses the term heterotopia to describe the place from which the mirror image, as it were, observes us. The look is directed at us from the place on the other side of the mirror’s surface. [2] Similar kinds of ‘other places’ have also arisen within the artists’ projects described here, from which we can look at the prevailing order. Each of these heterotopias is related in a clearly articulated way to society, power and capital.

Scenario

In 1993 a temporary bar opens at Friesenwall in Cologne. There are rumours that it’s got something to do with a work by the Argentine artist Rirkrit Tiravanija. The bar is a meeting place. Any performative aspect of the work is suppressed, allowing an ambiguous situation to occur. Everyone who comes ‘to look’ is taking part in a social and cultural exchange that creates a new model for passing time and questions the separation between art and everything else. Everyone in the bar soon begins to feel a sense of control and power, while attempting to verify the source of the events and think through their implications. Tiravanija refuses to claim or manipulate the event in any way, shape or form. Contemporary and colleague Liam Gillick qualifies this form of ‘outsiding’ (Tiravanija literally stands outside for most of the evening) as a critical strategy that successfully distances itself from the superficial presumptions about power and control that are typical of referential and illustrative methods. [3] The creation of this ambiguous experience reveals the possibility of other, multiple realities.

In 1998 Liam Gillick wrote the essay ‘Prevision. Should the Future Help the Past?’, [4] in which he describes how in Western cultures ‘scenario thinking’ is the dominant practice. Scenario thinking, like a present-day control mechanism, can be seen in politics, economics, film, TV and literature. More precisely, this scenario thinking is regarded as a critical means of guaranteeing the strategies of capitalism and the dynamics of the free market. This state of mind is prepared and reflected in TV and film (as the mass media that were relevant at that time). Instead of directly attacking or unmasking scenario thinking, the artists instead think ahead, suggests Gillick. They actively look for strategies that openly relate to society and which make it possible to indicate moments of change and doubt. In that same year curator Nicholas Bourriaud incorporated his experiences with these artists’ activities into Esthétique relationelle. [5]

In the exhibition Les Ateliers du Paradise by Philippe Perrin, Philippe Parreno and Pierre Joseph at the Air De Paris in Nice (1990) [6], the gallery was converted into a lounge where people could hang out; it was filled with luxury goods which could be used by visitors and artists: there was a Multigym, a rotating Bang & Olufsen TV, a hifi system, designer furniture and the summer collection by Jean-Paul Gaultier, as well as courses in Japanese, Arabic and tennis. The idea that an exhibition can intervene in the visitor’s experience is an almost obscene precept. Despite the explicit invitation to take part in the project, it is obvious to the visitors and artists that the material obsession being addressed actually has an alienating effect.

Magic

In 1973 Marcel Broodthaers published the book Magie. Art et Politique, which contained his open letter to Joseph Beuys. The letter was first published in the Dusseldorf newspaper Rheinische Post on 3rd October 1972 under the title Politik der Magie? Broodthaers starts with a letter from Jacques Offenbach to Richard Wagner in 1848. The handwritten letter, which he claims to have found in a deserted building in Cologne, is still fairly intelligible. Offenbach criticizes Wagner’s views on the alliance between art and politics.

Broodthaers copies out the letter in his own handwriting and changes a few words here and there. He calls on Beuys to discuss the circumstances of his artistic production. The letter is a reaction to the fact that Beuys did not withdraw from the Amsterdam-Paris-Düsseldorf exhibition in the New York Guggenheim Museum, after a work by Hans Haacke destined to be shown there was censored. According to the management at the Guggenheim Museum, no artistic merit could be attributed to the work that Haacke had submitted. The work in question included the Real Estate project, in which he wanted to present information about fraudulent dealings in real-estate companies concerning properties in Manhattan. The management were of the view that the work exceeded the boundaries of the institute. [7] Broodthaers suggests that there is a link between Beuys’ indifference to the Haacke conflict and his views on art and politics. [8] Using Offenbach’s words to Wagner, Broodthaers qualifies the political power that Beuys attributes to art as magic or illusion. As Beuys again explained in Documenta 5 in that same year, for him the artistic and the political are inextricably linked. He redefines state and society as artistic creations. Jeder Mensch ein Künstler! In a similar utopian scenario the attitude to power structures is more important than the actual position that people occupy in them.

By appropriating the letter from Offenbach to Wagner, Broodthaers acknowledges a reality in which various artistic and political positions make up history. The artist’s relationship to power is no different than that of other groups in society. Broodthaers’ strategy is to refute and break down the special political power and magical force that is attributed to art. It is more fruitful to underline the mercantile, dishonest nature of the art industry. Broodthaers’ ironic awareness is expressed in his very first solo exhibition in Galerie Saint Laurent in 1964, for which he had a faux-naïf artist’s statement printed on various sales brochures as invitations. In this invitation, entitled Moi aussi je me suis demandé si je ne pouvais pas vendre quelque chose… he claims that his conversion to art was for reasons of personal opportunism. [9]

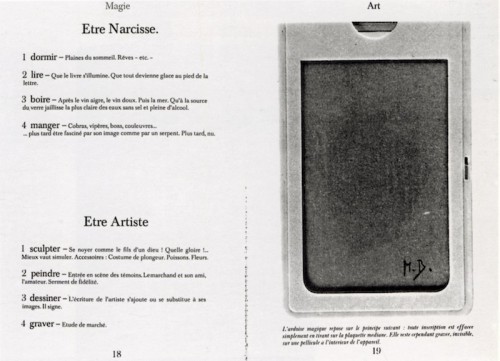

In part two of Magie. Art et Politique Broodthaers focuses on the relationship between art and magic. The text consists of two parts, ‘Être Narcisse’ and ‘Être Artiste’. The first part describes a few basic human actions (sleeping, reading, drinking and eating) using aphorisms from the Narcissus standpoint (dreams, mirrors, wine and snakes). In ‘Être Artiste’, Broodthaers deals with artistic actions like sculpting, painting, drawing and engraving. The facing pages all include a photo of a magic slate. [10] In the first photo Broodthaers’ initials form of a signature at the bottom right. In the second photo the initials appear in the middle of the drawing surface, like a sketch or work of art. In the third photo the slate is pulled half way out of its sleeve, so that the initials are already partially deleted, while in the fourth and final photo the slate is back in its sleeve and the initials have completely disappeared. Broodthaers’ initials remain etched on the celluloid of the sleeve however. Magic is always relative: the initials can be found in ‘the unconscious’ or ‘the memory’ of the device, as Broodthaers suggests in a reference to an observation by Freud on the mechanism of the magic slate. [11]

Curse

What is the value of pictures? The artistic programme of the Austrian artist Peter Friedl consists of overcoming the dictates of the visual. Friedl’s work deals with the problem of pictures that are related to a political and historical consciousness. Building on the strategies employed by the Conceptual Art movement of the sixties, Friedl extends the working domain of art to include the conditions and structures of the social, the economic and the institutional.

As with his works of art, Friedl also refers in his texts to multiple genres by means of revision. [12] He writes portraits and reviews (George Sand, Jean-Luc Godard, etc.), pens articles about theatre and film (Hermann Nitsch, Glauber Rocha, etc.). Moreover, he produces texts in which he reflects on his own work and texts that could be regarded as independent works of art. ‘The Curse of the Iguana: On Genre and Power’, ‘King Kong in Triomf’ and ‘Secret Modernity’ are the most representative as far as independent texts are concerned. Friedl brings all his material together in allegorical combinations that move back and forth between political-historical matters and questions on the role of the image and of art. The literary quality of the texts is present in the fact that Friedl manages to unite very diverse elements in a historical narrative by means of editing and intensification.

Friedl pulls no punches. Most texts are written during the years when social democracy, social liberalism and the Third Way were the dominant political ideologies. Art began to become much more interested in everything that was not (yet) art, and everything that was not art began to be interested in art. In an era in which politics, capital and art seemed to be tolerating each other, and seemed, in a critical context, even to be nourishing each other, Friedl was looking for ways to create space and a certain presence, exempt from absorption into one of the above. It’s the picture that has to pay the price. With the arrival of the post-Fordist service economy and the transition from a disciplinary society to a society of control, not least because of the fast-evolving information technology sector, the past and future lost their role in society. Pictures became beggars, repeatedly, ad nauseam, asking for our interaction, participation and emancipation. In the nineties art seemed to side definitively with the view that the design of a picture can always be reduced to capital. Most art, in Friedl’s view, ends up in the grip of scenario thinking. The latest artistic strategies instantly degenerate into genres.

In ‘The Curse of the Iguana’, Friedl looks specifically at the tension between art and politics. In this essay on colonial power and anti-colonial resistance movements, he uses the iguana as a metaphor for history. The iguana functions as an anonymous witness to the extremely violent political past on the island of Hispaniola in the Caribbean Sea. [13] Using mystifications and editing, Friedl gives an account of the long history of political events on the island, from the genocide of the Taíno by the Spanish conquistadors, through Trujillo’s dictatorial regime to those of Papa and Baby Doc. He also focuses heavily on anti-colonial opposition on the European continent, for example that of the German student leader Rudi Dutschke in the sixties. These post-war leftist movements were an immediate source of inspiration for a generation of artists in the seventies who founded the Conceptual Art movement. However, their mimicking of the office aesthetics of the First World had insufficient magical power to ward off the power of capital. Conceptual Art was a major source of inspiration for the principle of corporate design in the nineties. [14] The newest art allowed itself to be reduced to the latest art genre, by analogy with the popularity of western and gangster films.

Friedl is very clear about his opinion on the relationship between art and politics:

An aesthetic approach, as is well known, has the advantage that you can live with defeats more easily. That’s a problem today. You don’t commit yourself to particular political actions, because you can predict what the power relationships are, and one doesn’t want to be on the losing side right from the beginning. [15]

The inclusion of the user in a world of standard scripts and instant design is summarised by Friedl in the modern picture of the painter of advertising billboards at the Dominican Lago Enriquillo (the site of the last anti-colonial revolt by the Taíno). The painter creates the advertising messages with beautifully coloured, handmade copies of the original grotesque office fonts. ‘Trompe-l’oeil means the art of not observing in detail’, adds Friedl.

Ghosts

The work of the Brussels artist Sven Augustijnen is the result of factual observations. If you wander along Place du Trône, past a huge statue of Leopold II astride a horse, and then continue on through the streets of the Congolese Matonge district, as far as the house near Avenue Louise where Karl Marx wrote the Communist Manifesto, you will encounter the ghosts of Leopold II, Lumumba and Marx.

Half a century after Patrice Lumumba’s death and twenty years after the Knight Jacques Brassinne de la Buissière completed his doctoral thesis, Sven Augustijnen again gave Brassinne the opportunity to put his case in the film and exhibition Spectres. Brassinne is a former Belgian diplomat who was working in the Congo at the time of Lumumba’s execution in 1961. In 1990 he published a historiographical PhD thesis on the murder of Lumumba. Brassinne intended to show that it was a ‘Bantu matter’, but in 1999 the sociologist Ludo De Witte claimed to have found proof, on the basis of the same documents, of the involvement of the Belgians in the death of Lumumba. Less than a year later a parliamentary investigation was opened. The final conclusion of the committee reported that ‘some Belgian government officials and other Belgian parties bore a moral responsibility’. In 2002 the Verhofstadt government offered an apology to the family of the first Congolese prime minister and to the Congolese people. Sven Augustijnen’s request to Jacques Brassinne to take another look at his vision and account of the facts was eagerly welcomed by Brassinne, who saw it as an opportunity to reclaim the ghost that he himself had allowed to escape. [16]

In the film Brassinne visits the relatives of the main protagonists. He also goes to Congo, to the places where Patrice Lumumba spent his final hours and was killed. Augustijnen records the scenes in an apparently nonchalant and personal way, whilst adhering to the codes of cinema vérité.

In addition to the film there is an exhibition displaying the documents collected by the historian. We are invited to look at a series of photos of various expeditions to the place of execution (it was Brassinne himself who discovered the site in 1989). There is a glass case containing his doctoral thesis, his book, old personal photos showing Brassinne in the company of Congolese leaders, a radio interview, and even a flag of the Katangese separatist movement. For Brassinne these documents are pieces of evidence and serve to support his account of the facts. But do they retain this unambiguous function when in the context of an exhibition in a centre for contemporary art? [17]

An impressive scene in the film is the moment when the guide, Brassinne, goes to visit the family of Lumumba in Congo. During an animated conversation between Jacques Brassinne and Pauline Opanga Onosamba, Lumumba’s widow, the camera pans out, allowing us to see the other members of the family. Just as the camera points at the door, a young man enters the room. He looks into the camera and starts. It is one of Lumumba’s sons: the likeness with his father is astonishing. For a second it is as if Lumumba is looking at us through the eyes of his son, and has caught us spying. Although the film initially comes across as a fairly conventional documentary, it is an art film. We are not watching from a journalistic or scientific perspective: our motives are by definition impure.

This impurity also applies to Jacques Brassinne and the other protagonists in the film. The former diplomat dissembles, together with the son of Harold d’Aspremont Lynden, who was Belgium’s Minister for African Affairs in 1961, on the notorious telex in which it was suggested that a ‘definitive elimination’ of Lumumba was desirable. We see how, at the grave of Moïse Tshombe in Brussels, Brassinne says nothing in front of Tshombe’s daughter Marie about her father’s presence at the murder of Lumumba. We also see the historian go to the site of the execution in the middle of the night and declare in the car headlights with a statement of the case in his hands that the Belgians had nothing to do with the actual execution (a scene based on an idea by Brassinne himself). Immediately before this scene Brassinne and the camera team meet a man on the country lane leading to the site of the execution. The man asks them what they are doing there. He delicately observes that anyone on the road at this time of the day is hardly likely to be up to any good.

In Spectres we see the distance between history and memory opening up. Not just in the way in which the central character wrote history and looks back at it, but also in the way Augustijnen does the same thing. The historian can’t get the ghost back in the box. Le spectre, le revenant, keeps coming back. [18]

Intolerance

Just as in Spectres we are confronted solely by historical artefacts, in 2010 in the Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin Willem de Rooij presented Intolerance, an installation with exclusively historical objects. It is a confrontation between eighteen paintings by the seventeenth century bird painter Melchior d’Hondecoeter and several rare Hawaiian feather articles from the eighteenth and nineteenth century, including some brought back to Europe by Cook’s last expedition. The two types of object now find themselves together for the first time in the same space, on opposite sides of a high grey wall with sunken windows, which divides the dimmed space of the Neue Nationalgalerie into two parts. The confrontation is accompanied by a website, a visitor’s guide and a three-part catalogue containing academic studies on d’Hondecoeter, Hawaiian feather objects and De Rooij’s work.

Open to multiple interpretations, Intolerance can be seen as a three-dimensional collage. It is a reflection on the limits of exhibition spaces and institutional practices, as well as being a visual essay on the triangular relationship between early world trade, interculturalism and forces of mutual attraction. The two types of object that form the nexus of Intolerance were originally produced to represent the establishment. They served as paraphernalia of the ruling class. Their value supported the existing power structures of that time.

Two works from the collections of the State Museum of Berlin formed the starting point for Intolerance: a likeness of the God of War Kuka’ilimoku, made of bird feathers, dog’s teeth and human hair, from the Ethnological Museum in Dahlem, and a painting of Melchior d’Hondecoeter that belonged to the Gemälde gallery, Pelikan und andere Wasservögel in einem Park (Pelican and Other Waterfowl in a Park). By bringing together these two works in the Neue Nationalgalerie, De Rooij overcomes art history classifications and disciplinary demarcations. At a time when the cultural climate is increasingly the domain of private investors, Intolerance forces us to think of the relevance and use of public collections. [19]

The meeting evokes unexpected parallels. For example, the birds that d’Hondecoeter portrayed in such an incredibly lifelike way are more than just protagonists in situations of tension, threat and conflict. The birds presented are exotic, rare, valuable, and as such desired objects among the elite. At the same time, they represent human appetite and express mutual tensions, which could be understood as a commentary on the young Dutch Republic, which in a short time evolved into a world power by means of colonial expansion and international trade, but which didn’t quite know what to do with its new-found status. As allegories for uncertainty and danger, they are equivalent to the scary yet fascinating head of Kuka’ilimoku. The Dutch critic Dominic van den Boogerd made a sharp observation:

One association is difficult to suppress: the uncertainty, tension and threat that dominate Intolerance are suspiciously similar to the political turbulence in today’s Netherlands on the subjects of national identity, Islam and immigration. It’s as if the Kuka’ilimoku season has dawned once again. [20]

Mimicry and commitment

In 2005 Jonas Staal anonymously erected a series of 21 ‘roadside memorials’ consisting of white roses, candles, cuddly toys and framed portraits and photo collages with images of Geert Wilders. Wilders felt threatened by this series of displays and made a complaint to the police. During their enquiry, the various police spokesmen made it clear that they were not sure if they were dealing with a form of threat or with a show of support for the politician. Nevertheless, after owning up to the project Staal, was arrested and prosecuted over the course of three years for ‘death threat to a member of the Dutch Parliament’. This resulted in two court cases, which Staal put together in what he called a total production: the project entitled De Geert Wilders werken 2005-2008. A year after the last court case, which for a second time resulted in acquittal, one question keeps coming back at Staal: is he not partially responsible for Wilders’ success? Is it not the case that this series of works – focusing on the relationship between the phenomenon of the roadside memorial and the importance of cult status in populist political movements – is a basis for Wilders’ public martyrdom and status as an untouchable media icon? [21]

Staal responds with a whole-hearted ‘yes’ to this question. He gives a more detailed explanation in Post-propaganda, in which he describes his political commitment as a logical consequence of the aspect of negotiation that is central to the democratic political ideology: politics and art are obliged to be each other’s co-authors.

In a 1930s anthropological study on the Kuna Indians in Panama, reference is made to the use of wooden dolls during healing rituals. What is remarkable about these dolls is that they do not look like Indians or demons, but, judging by the clothing, the headgear and the sharp noses, are in the guise of the European colonisers. Anthropologist Michael Taussig defines the term mimesis as a form of mimicry: it is the possibility of copying the original and thereby taking over its soul and its agens. The copy is in fact the externalisation of a certain mimetic knowledge; proof that the model was screened, sniffed at and taken into possession. [22]

The logic followed by Jonas Staal is probably what Taussig would call that of mimetic excess. [23] Staal, as an imprisoned ape, gives his report to the academy: he is aping the human tendency to ape. This is an upward spiral of transgression. Staal makes no statement about which policies he supports, but engages in the externalisation of the ambiguity, the alienation and the conflicts that characterise the democratic process. He has no desire to continue subjecting himself to party politics. Staal wants to converge with the political battlefield on the basis of a bogus demagogic argument. To be political commitment.

The French writer Roger Caillois delivers a telling description of the zero point of such a desire:

He is similar, not similar to something, but just similar. And he invents spasms of which he is the convulsive possession. [24]

Epilogue: Gerhard Richter

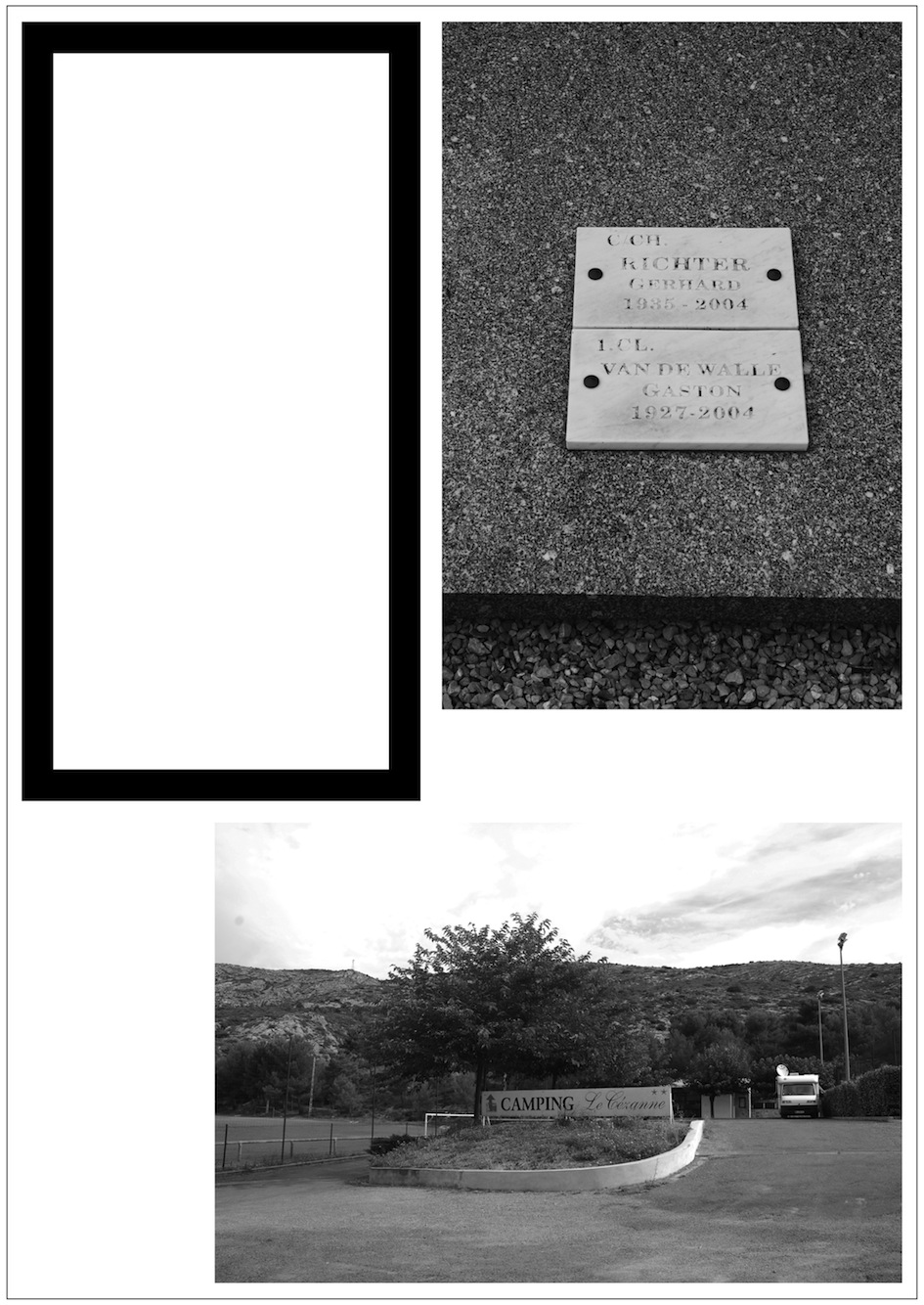

In a quiet area 25 km from Aix-en-Provence, at the foot of Mont Sainte-Victoire, there is a campsite called Le Cézanne. Between 1902 and 1906 this mountain was frequently depicted in the works of Paul Cézanne. In 1901 the French painter bought a country estate to the north of Aix, where he had his studio. From there Cézanne could see the mountain as well as the intervening valley.

If I come further down the slope at the foot of the mountain, I come across a burial ground for French Foreign Legionnaires near the campsite. As I read through the names on the soldiers’ headstones, one name stands out: Gerhard Richter, who died in 2004. Alongside Gerhard Richter the famous German visual artist, there is – manifestly – a Gerhard Richter who was an entirely different being.

I stare at the grave. Then, once more, I hear the sound of children playing on the campsite.

Mont Sainte-Victoire, juillet 2011 © Robin Vanbesien

Translated from the Dutch by Gregory Ball

Originally published in Dutch in the Belgian literary journal nY, #11 (Autumn 2011).

Check Robin Vanbesien’s website.

Notes

[1] The open call on berlinbiennale.de has since been removed. However, copies can still be found on the Internet. ↑

[2] Michel Foucault, ‘Of Other Spaces’ (1967), online. ↑

[3] Liam Gillick, ‘Outsiding. Rirkrit Tiravanija’s Places’, in: Proxemics. Selected Writings (1988–2006), ed. Lionel Bouvier, Zürich & Dijon, JRP|Ringier & Les Presses du réel, 2006, p. 269 ↑

[4] In: Proxemics, pp. 193-211 ↑

[5] See Relational Aesthetics, Dijon, Les Presses du réel, 2002. ‘… most of the artists [Bourriaud] describes, including Gillick, reject his summations. This is mainly due to a sense that in association with relational aesthetics their art tends to be watered down to a cartoon version of interactivity and not enough attention is given to its material conditions.’ (Monika Szewczyk, ‘Introduction’, in: Meaning Liam Gillick, ed. Monika Szewczyk, Cambridge/London, The MIT Press, 2009, pp. xix-xx) ↑

[6] See, amongst others, Liam Gillick, ‘Les Ateliers du Paradise. Air de Paris, Nice’, in: Proxemics, pp. 173-177 ↑

[7] Deborah Schultz, Marcel Broodthaers. Strategy and Dialogue, Bern, Peter Lang, 2007, p. 246 ↑

[8] See Stefan Germer, ‘Haacke, Broodthaers, Beuys’, in: October, no. 45, 1988, The MIT Press, pp. 63-75, online. ↑

[9] Schultz, Marcel Broodthaers, p. 60 ↑

[10] The magic slate (in Freud: Wunderblock) as described here, no longer exists. A modern-day equivalent is the magic/magnetic drawing board. ↑

[11] Schultz, Marcel Broodthaers, p. 265. Cf. Sigmund Freud, ‘Notiz über den “Wunderblock”’, online. ↑

[12] In 2010, a compilation of Friedl’s texts and interviews from the period 1981-2009 was published on the initiative of curator Anselm Franke. See Peter Friedl, Secret Modernity. Selected Writings and Interviews 1981–2009, ed. Anselm Franke, Berlin/New York, Sternberg, 2010 ↑

[13] ‘Iguanas are as old as they look. They are said to have a nearly unmatched ability to adapt to various environments from hot desert regions to tropical rainforests, the equator to so-called temperate zones, seacoast to snowline.’ (Peter Friedl, ‘The Curse of the Iguana: On Genre and Power’, in: Secret Modernity, p. 124) ↑

[14] In his design of the catalogue for the Dream City exhibition in Munich in 1998, Friedl appropriates the corporate design of the main sponsor, Siemens. ↑

[15] ‘A Conversation with Roger M. Burguel’, in: Secret Modernity, p. 155 ↑

[16] Ronald Van de Sompel, ‘What a Day for a Daydream’ in: Newspaper Jan Mot, issue 15, no. 77, pp. 3-5 ↑

[17] A full reproduction of Jacques Brassinne’s archive of material evidence is published in the catalogue of the exhibition. ↑

[18] During postproduction of the film, on 17th January 2011, Patrice Lumumba’s three sons, François, Roland and Guy, started legal proceedings against eleven Belgians, including Jacques Brassinne himself, for involvement in the death of Lumumba. ↑

[19] A paraphrase of the accompanying text in the exhibition, which is also available online. ↑

[20] Willem de Rooij: Intolerance’, in: De Witte Raaf, no. 148, 2010, online (in Dutch). ↑

[21] As described by Jonas Staal in ‘Post-propaganda’; in: De Groene Amsterdammer, 30 October 2009, p. 32, online (in Dutch). ↑

[22] See Michael Taussig, Mimesis and Alterity: A Particular History of The Senses, Routledge, New York, 1993 ↑

[23] A logic that is gaining in popularity in the Dutch arts: see also the artistic strategies of BAVO (Gideon Boie and Matthias Pauwels) and Renzo Martens, among others. ↑

[24] Roger Caillois, ‘Mimicry and Legendary Psychaesthenia’ [1935], in: Michael Taussig, Mimesis and Alterity, p. 34 ↑